Cuba: Geology and regional setting

| Geology of Cuba | |

| |

| Series | Studies in Geology |

|---|---|

| Author | Georges Pardo |

| Link | Web page |

| Store | AAPG Store |

The geology of Cuba has been a challenge to geologists because of features such as the presence of well-preserved Jurassic ammonites, the rich Tertiary foraminiferal faunas (including remarkable Paleogene orbitoids), the gigantic Upper Cretaceous rudistids, the spectacular limestone Mogotes of Pinar del Rio, the extensive outcrops of ultrabasic igneous rocks, the chromite and manganese deposits, and the extraordinary structural complexity. In addition to these features, the numerous petroleum seeps, many of them coming out of basic igneous rock, have attracted much attention.

Regional setting

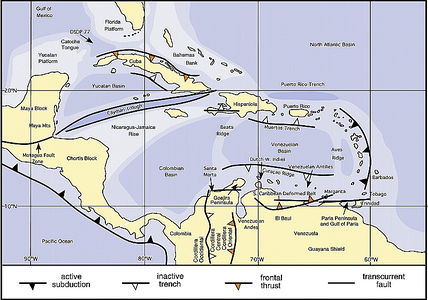

Cuba is the largest of the Caribbean islands and has an arclike shape, concave to the south (Figure 1). This shape has tempted some authors to call Cuba an island arc. The truth is much more complex. The broad and deep Straits of Florida separate Cuba from Florida, and the narrow, and relatively shallow, Nicholas and Old Bahama channels separate Cuba from the Bahamas. To the northwest, Cuba adjoins the Gulf of Mexico and is separated from the Yucatan Platform by the narrow but deep Yucatan Channel. To the south, the Yucatan Basin appears to be enclosed between Cuba to the north and the Cayman Ridge, which is the westward continuation of the Sierra Madre in the southern Oriente province. Cuba, the Cayman Basin, and the Cayman Ridge appear to constitute a physiographic province between the stable margin of the North American craton and the highly mobile Caribbean Basin. This province is separated from the Chortis-Nicaraguan rise block, including Jamaica and Hispaniola, by the east to west pull-apart basin of the Cayman trough, whose spreading center has been recording the eastward migration of the Caribbean plate since the late Eocene.

Figure 1 Regional setting of Cuba.[1]

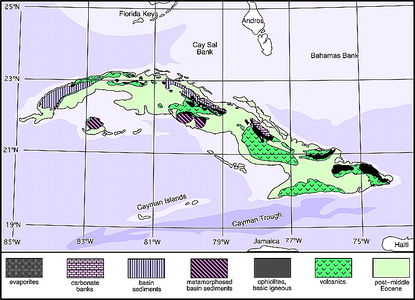

Figure 2 Cuba generalized geologic map.[1]

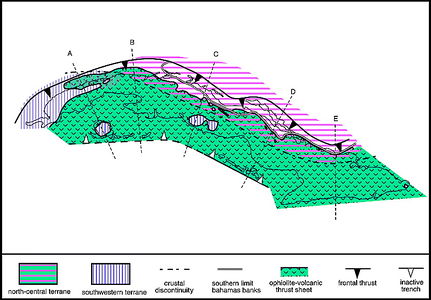

Figure 3 Generalized structure of Cuba.[1]

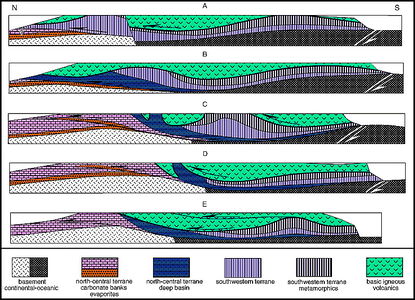

Figure 4 Generalized cross sections of Cuba.[1]

Over most of its length, the northern coast of Cuba is the dividing line between stable conditions (at least since the Middle Jurassic) to the north and west and very complex ones to the south. Although it is geologically deformed (Figure 2), the part of the northern coast of Cuba extending from eastern Natanzas to western Oriente belongs to the Florida-Bahamas carbonate bank province. To the south, in part under an upper Eocene or younger cover, is a relatively narrow belt, 45-160 km (28-99 mi) wide, of intensely folded and faulted Middle Jurassic to middle Eocene rocks consisting, from north to south, of:

- the north-central sedimentary terranes, characterized by very thick platform carbonates and evaporites on the north and a relatively thin section of platform to pelagic carbonates and cherts on the south;

- the ophiolitic basic igneous-volcanic (called igneous-volcanic because of being a mixture of intrusive and volcanic (extrusive) rocks with a general predominance of volcanic rocks) terranes, with ultrabasic intrusive rocks, many types and great thicknesses of basic, basaltic to andesitic volcanic rocks, volcanic-derived sediments, and granodioritic intrusives, and

- the southwestern sedimentary terranes, with primarily thin stratigraphic sections of platform to pelagic carbonates and cherts but locally with great thicknesses of older, continental-derived sandstones and shales showing various degrees of metamorphism.

The most striking feature about the geology of the island is the great disparity between the ophiolite-volcanic sequence of the basic igneous-volcanic terranes and the sedimentary sequences of the north-central and southwestern sedimentary terranes. Except for a few notable cases, essentially no relationship exists between these sedimentary and igneous terranes, which you may read about at essay writing service not to get confused by the naturally arising question how these types of terrains appeared to create one union arises. There has been much argument about how the terranes came into contact and became structurally mixed, but it is generally accepted today that the ophiolite-volcanic sequence is totally allochthonous. Figure 3 shows a map of Cuba's major structural features and terrane distribution, and Figure 4 shows, in cross section, the structural relations between the various terranes.

Although Cuba is now part of the North American continent, it is a remnant of a Cretaceous to early Tertiary orogenic belt that has been preserved because of the local configurations of the North American and Caribbean plates. As a consequence, Cuba exposes sequences of Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous nonvolcanic pelagic sediments that are rare, if not unique, in the Caribbean as well as in North, Central, and South America. However, Cuba has facies and faunal similarities with equivalent strata of the Tethys region, specifically the Alps and Italian Apennines.

Similarities and differences exist between the Jurassic–Cretaceous sedimentary sections of Cuba and other areas in the region.

Nannoconus biomicrites containing aptychi, identical with the Neocomian of Cuba (and the Alps), are present in southern Belize, south of the Maya Mountains;[2][3] in Mexico, in the Lower Cretaceous of the Sierra Madre Oriental; and in the coreholes of Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 77 in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico (this type of Cretaceous sediment is widespread in the deep Atlantic Ocean).

In the Maya block of the Yucatan Peninsula (and northern Belize, north and west of the Maya Mountains), all the reported carbonates belong to the Cretaceous Coban and Campur Formations. They are similar to the bank carbonates of the Bahamas Platform and, therefore, are similar to the bank carbonates of north-central Cuba. The Coban Formation grades northward into a thick evaporite section, which overlies the dominantly red clastics of the Todos los Santos Formation, that has been compared to the San Cayetano Formation of Cuba's Pinar del Rio. Carbonates exist in the highly deformed Motagua fault zone, in central Guatemala, but similarity to carbonates found in Cuba is uncertain.

The clastic El Plan Formation in the Chortis block of Central America in Honduras has been compared to the San Cayetano Formation. It shows lithologic and paleoenvironmental similarities. However, its Triassic to Middle Jurassic age, although somewhat in doubt, makes it older than the San Cayetano. El Plan Formation is a very controversial unit because all the contacts with other units are tectonic.

Present in much of Central America is a Cretaceous carbonate section unlike the Cuban carbonates of the same age. It consists of Neocomian to Cenomanian, mostly shallow-water Yojoa Group limestone underlain by Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous clastics of the Honduras Group and overlain by the Upper Cretaceous Valle de los Angeles Group that consists mostly of red beds.

Similar to the northeastern Cuban evaporites are Upper Jurassic(?) to Lower Cretaceous Maraval evaporites in the Paria Peninsula and Gulf of Paria, in the southern Caribbean between Venezuela and Trinidad. The metamorphosed clastics and marbles of the Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous Caracas series in northern Venezuela have some similarities to Cuba's southern metamorphic massifs. In addition, the thick section of Upper Jurassic clastics of the Cosina Group (overlain by fossiliferous Neocomian carbonates of the Kesima, Palare, Moina, and Yaruma Formations) in the Guajira Peninsula have similarities to the San Cayetano of Cuba's Pinar del Rio. Some similarity exists between the Orbitolina-bearing reef carbonates of Cuba, Venezuela's Lower Cretaceous Cogollo Group and Cantil Formation, and contemporaneous facies of the Florida-Bahamas Platform.

Close similarities exist between the Mesozoic igneous intrusive and associated volcanic rocks of Cuba and those of the Caribbean.

Ophiolites are common throughout the Caribbean and extend from the Motagua fault zone, between the Maya and Chortis block, to Puerto Rico. They also form the floor of the Cayman Trench. These rocks are also common along the northern coast of South America from Tobago to the Guajira Peninsula, although they are not as intensely serpentinized as in the northern Caribbean. Cuba's outcrops of ultrabasic rocks are the most extensive in the region.

Similarities exist between the Caribbean and the Cuban Upper Cretaceous volcanic and associated intrusive rocks. The Cuban Upper Cretaceous granodioritic intrusion has counterparts outcropping in Hispaniola, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico in the north (where the intrusive's ages range into the Paleogene) and in Aruba, the Venezuelan Antilles, and the Aves Ridge in the south. Volcanics containing a characteristic fauna of Acteonella, large rudists (Hippurites), and orbitoids are present in Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, the Dutch West Indies, and northern Venezuela, suggesting a connection between the various parts of the volcanic province.

Other than the Yucatan Basin, Cuba is probably the only place in the Caribbean with complete sections representative of the early Caribean region after the separation of North and South America and before the formation of the present Caribbean plate in the Paleogene.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Pardo, G., 2009, The geology of Cuba: AAPG Studies in Geology 58, 73 p.

- ↑ Flores, G., 1952, Geology of northern British Honduras: AAPG Bulletin, v. 36, p. 404-413.

- ↑ Schafhauser, A., W. Stinnesbeck, B. Holland, T. Adatte, and J. Remane, 2003, Lower Cretaceous pelagic limestones in southern Belize: Proto-Caribbean deposits on the southeastern Maya block, in C. Bartolini, R. T. Buffler, and J. Blickwede, eds., The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics: AAPG Memoir 79, p. 624-637.