Carbonate diagenetic stages

| Exploring for Oil and Gas Traps | |

| |

| Series | Treatise in Petroleum Geology |

|---|---|

| Part | Predicting the occurrence of oil and gas traps |

| Chapter | Predicting reservoir system quality and performance |

| Author | Dan J. Hartmann, Edward A. Beaumont |

| Link | Web page |

| Store | AAPG Store |

Stages affect porosity

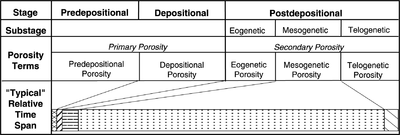

Three major geologic stages determine the porosity of carbonate rocks:[1]

- Predepositional

- Depositional

- Postdepositional

The predepositional stage is the time from when sedimentary material first forms to when it is finally deposited. Porosity created during the predepositional stage is mainly chambers or cell structures of skeletal grains or within nonskeletal grains such as pellets or ooids.

The depositional stage is the relatively short time involved in the final deposition at the site of ultimate burial of a carbonate sediment. Most porosity formed is intergranular, although some can also be framework.

The postdepositional stage is the time after final deposition. All the porosity that forms during this stage is diagenetic or secondary in origin. Diagenetic processes are related to changes in water chemistry, temperature, pressure, and water movement.

Time-porosity table

The table and chart in Figure 1 list time–porosity terminology and relationships.

Postdepositional substages

The postdepositional time period, which can be quite long (millions of years), can be divided into three substages:

- Eogenetic (early)

- Mesogenetic (middle)

- Telogenetic (late)

The eogenetic substage (early diagenetic period) is the time from final deposition to the time when the sediment is buried below the zone of influence from surface processes. The eogenetic zone extends from the surface to the base of the zone of influence of surface processes. Even though the eogenetic substage may be geologically brief and the zone thin, the diagenesis that occurs is more varied and generally more significant than any other substage. Eogenetic processes are generally fabric selective. The major porosity change is reduction through carbonate or evaporite mineral precipitation. Internal sedimentation also reduces porosity. Although minor in comparison, the most important porosity creation process is selective solution of aragonite.[1]

The mesogenetic substage (middle diagenetic) encompasses the time when the sediment is out of the influence of surface diagenetic processes. Cementation is the major process. Porosity obliteration occurs when mosaics of coarsely crystalline calcite precipitate in large pores. Pressure solution occurs at higher pressures.

The telogenetic substage (late diagenetic) occurs when sedimentary carbonates are raised to the surface and erosion occurs along unconformities. The telogenetic zone extends from the surface to the point where surface processes no longer influence diagenesis. Solution by meteoric water creates porosity. Internal sedimentation and cementation by precipitation from solution destroy porosity.

Path of diagenesis

The parts of the path of diagenesis that a carbonate sediment follows determine the evolution of its porosity. Figure 2 summarizes the diagenesis that occurs along the path.

See also

- Predicting carbonate porosity and permeability

- Carbonate facies

- Carbonate diagenesis

- Early carbonate diagenesis

- Basics of carbonate porosity formation and preservation

- Sea level cycles and carbonate sequences

- Sea level cycles and carbonate diagenesis

- Sea level cycles and climate

- Sequences during low-amplitude, high-frequency cycles

- Sequences during moderate-amplitude, high-frequency cycles

- Sequences during high-amplitude, high-frequency cycles

- Predicting carbonate reservoir location and quality

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Choquette, P. W., and L. C. Pray, 1970, Geologic nomenclature and classification of porosity in sedimentary carbonates: AAPG Bulletin, vol. 54, no. 2, p. 207–250. Classic reference for basic concepts regarding carbonate porosity.

- ↑ Harris, P. M., C. G. St.-C. Kendall, and I. Lerche, 1985, Carbonate cementation--a brief review, in N. Schneidermann and P. M. Harris, eds., Carbonate CEments :SEPM Special Publication 36, p. 79-95.