Seal capacity of breached and hydrocarbon-wet seals

| Exploring for Oil and Gas Traps | |

| |

| Series | Treatise in Petroleum Geology |

|---|---|

| Part | Predicting the occurrence of oil and gas traps |

| Chapter | Evaluating top and fault seal |

| Author | Grant M. Skerlec |

| Link | Web page |

| Store | AAPG Store |

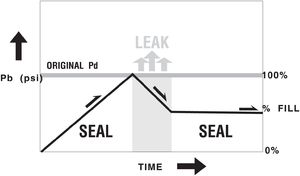

Hydrocarbon column heights may not be related only to the displacement pressure of the top seal. Once a seal has been breached and hydrocarbons forced through the seal, theoretically the hydrocarbon column will shrink until the buoyant pressure equals the displacement pressure and the system again seals. In practice, however, hydrocarbons continue to flow through the seal until there is no longer a continuous hydrocarbon filament. Although the process is not completely understood, laboratory studies suggest that flow continues until the hydrocarbon column shrinks to half its original height.[1][2]

Most traps half full

The preceding discussion suggests that in basins where there is charge sufficient to fill all traps to maximum seal capacity, traps limited by the capillary properties of intact top seals should be half full.[4] Rather than the hydrocarbon columns matching the displacement pressures of the seal, all filled traps would have leaked hydrocarbons until the buoyant pressure (Pb) is half the displacement pressure (Pd). Continued charging of traps after initial fill could result in larger hydrocarbon columns. Only in basins with insufficient hydrocarbons to fill all traps to the maximum seal capacity, or with charge after leakage, would there be a large number of traps greater than half full.

Figure 1 illustrates the fill history of a trap with some finite seal capacity that has been filled to seal capacity and then leaked. The final hydrocarbon column is half of that predicted by the displacement pressure of the top seal.

Water wet vs. oil wet

Estimates of seal capacity from measured displacement pressures commonly assume the seal is water wet. Oil-wet seals may be more common than we think. Organic-rich shales, a common top seal, are probably oil wet.[5] Similarly, episodic leakage of hydrocarbons through a seal may alter the seal capacity.

See also

- Seal capacity: pitfalls and limitations of estimation

- Displacement pressure of a seal: difficulty of characterization

- Displacement pressure: does the theory predict reality?

- Saturations required for hydrocarbon flow

- Hydrodynamic flow and pressure transients

References

- ↑ Roof, J. G., 1970, Snap-off of oil droplets in water-wet pores: SPE Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 85–90.

- ↑ Schowalter, T. T., 1979, Mechanics of secondary hydrocarbon migration and entrapment: AAPG Bulletin, vol. 63, no. 5, p. 723–760.

- ↑ Boult, P. J., 1993, Membrane seal and tertiary migration pathways in the Bodalla South oilfield, Eronmanga Basin, Australia: Marine and Petroleum Geology, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 3–13, DOI 10.1016/0264-8172(93)90095-A.

- ↑ Watts, N. L., 1987, Theoretical aspects of cap-rock and fault seals for single and two-phase hydrocarbon columns: Marine and Petroleum Geology, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 274–307, DOI 10.1016/0264-8172(87)90008-0.

- ↑ Cuiec, L., 1987, Wettability and oil reservoirs, in Kleppe, J., Berg, E. W., Buller, A. T., Hjemeland, O., and Torsaeter, O., eds., North Sea Oil and Gas Reservoirs: London, Graham and Trotman, p. 193–207.