Super basins

An Entry from the AAPG 2021 Middle East Wiki Write Off![edit]

by Gabriel Giacomone (Pluspetrol S.A.), María Eugenia Novara (Pluspetrol S.A.), and Josefina Vizcaíno (Binghamton University)

Super basin is a modern term referring to sedimentary basins where the cumulative production and the remaining recoverable resources are higher than 5 billion BOE.[1] [2] They are characterized by having more than one petroleum system, a solid field infrastructure and abundant data sets for studies. The access to the market is also an essential element in this definition.[1][2]

In a world demanding more energy every decade, ideas involving lower costs and reduced environmental impacts are crucial to optimize hydrocarbon production. Although certain favorable geological conditions are needed for basins to become super basins, a key for this transformation includes changes in paradigms and technology advances, which increase the prospectivity and production of fields.[1][2]

Geology of super basins[edit]

Oil and gas industry activity depends on technical, environmental, commercial and operational factors; among these, geological challenges and science innovations play an important role. When unconventional resources were introduced to geological models in mature basins, and horizontal drilling was an economic alternative for reaching reservoirs, this industry was propelled in markets. The Super Basin concept reflects the necessity of new insights into mature areas and large fields production, which implies reviewing previous paradigms and creating and adapting others.[2]

Tectonic setting[edit]

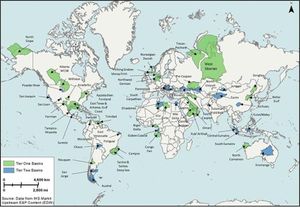

Super Basins are associated with rifts, passive margins, foreland and intracratonic tectonic settings. Most are Mesozoic-aged (J-K), although there are Paleozoic-age examples.[1][2] Understanding the stratigraphy and timing of these settings help predict the localization of the petroleum system components.[1][2] Globally, 31 basins have been identified within the super basin category so far (Figure 1).[1][2] Many of them (23) are in onshore locations, such as the Permian Basin in the United States and Neuquén Basin in Argentina.[2] However, significant offshore basins like the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea Basin are also included in this category. Based on the incremental recoverable oil (billions of barrels), super basins are grouped in regions. Leading the list is the Middle East, followed by North America, Latin America, Africa, Commonwealth of Independent States, Far East, Australasia and Europe.[1]

Stratigraphy[edit]

Large clinoform geometries (100s to 1000s m) are a classic feature in many super basins, like in Neuquén, West Siberia, Alaska North Slope, Permian, and Western Canadian basins. These geometries are a response of the depositional environments and the configuration of the basin in which they occur. The recognition and interpretation of these clinoforms can lead to a better understanding of the different elements of the petroleum system, e.g. the bottomsets of the clinoforms can be associated with deep-water shales with source rock potential and associated turbidites that might act as reservoirs.

Understanding factors like anoxic events, sea level and climate fluctuations help predict and insight the distribution of source rocks.[3][4][5] Source rock mapping can enhance productive super basins evaluations, potentially identify deeper or underappreciated petroleum systems, and help anticipate new plays in emerging super basins.[6][7]

Structural traps have historically driven exploration and have been responsible for most reserves in super basins. However, stratigraphic and combined trap discoveries have significantly increased over the last 20 years and are now the most prospectable plays along with the unconventionals. Historically, these traps have only comprised 10% of giant fields. [8] From 1988 to 1999, hydrocarbon volumes in stratigraphic traps increased to 15%, driven by advances in 3D seismic imaging. [9] However, since 2000, resources attributed to giant stratigraphic and combined traps have grown to 60%, primarily related to thick, evaporite-sealed carbonate reefs and buildups that effectively form four-way dip structures in the Caspian Basin, Egypt, Brazil, and Turkmenistan. [2] Large passive margin turbidite fans, channels, and contourites are the second-most significant stratigraphic play type. [2] Many tectonic uplifts create unconformities that can be correlated within and between other super basins; they can play a major role, controlling pinch-outs, truncations, wedge belts of porosity, and migration pathways [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]. In super basins with carbonate reservoirs, unconformities can dramatically dissolve and create karst reservoir fabrics. [15] [16] [17] [18]

After the dramatic decrease in the conventional oil discoveries in 2010, the organic-rich shale revolution, offshore fields, the use of modern technologies and a high oil price positioned the hydrocarbon industry in a new and better place in the market. [1] Unconventional reservoirs are part of a new era requiring original ideas. [1] They are characterized by organic rich shales or tight (low permeability) carbonates and sandstones, and they were previously only considered to work as source rocks or seals. Petrophysically, they present porosities < 10% and permeabilities in the nanodarcy range. Studies showed that organic rich shale rocks retain more hydrocarbon than what they actually expelled, therefore, their importance lies in their large production potential. [1] When this new understanding of source rocks was established in the geoscientist community, recoverable oil rates increased, as new reservoirs were contemplated in geological models.

Thinking outside the box has always been a quality explorers needed and it is most important in super basin exploration; it has given the opportunity to review marginal and old targets that were bypassed before this revolution. [1] [2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Fryklund, B., and P. Stark, 2020, Super basins-New paradigm for oil and gas supply: AAPG Bulletin, v. 104, p. 2507-2519.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Sternbach, C.A., 2020, Super basin thinking: Methods to explore and revitalize the world’s greatest petroleum basins: AAPG Bulletin, v. 104, p. 2463-2506

- ↑ Vail, P. R., and R. M. Mitchum, 1979, Global cycles of relative changes of sea level from seismic stratigraphy, in Geological and geophysical investigations of continental margins: AAPG memoir 29, p. 469–472.

- ↑ Haq, B., J. Hardenbol, and P. R. Vail, 1987, Chronology of fluctuating sea levels since the Triassic: Science, v. 235, no. 4793, p. 1156–1167, doi:10.1126/science.235.4793.1156.

- ↑ Sorkhabi, R., 2016, Rich petroleum source rocks, GeoExPro, v. 6, no. 6, p. 16–22.

- ↑ Dolson, J. C., 2016, Understanding oil and gas shows and seals in the search for hydrocarbons: Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 486 p., doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29710-1.

- ↑ Dolson, J. C., 2017, Hunting for NULFs: GeoExPro Magazine, v. 14, no. 2, p. 30–33.