East Breaks deep-water exploration strategy

| Exploring for Oil and Gas Traps | |

| |

| Series | Treatise in Petroleum Geology |

|---|---|

| Part | Critical elements of the petroleum system |

| Chapter | Sedimentary basin analysis |

| Author | John M. Armentrout |

| Link | Web page |

| Store | AAPG Store |

The lateral shifting of depositional lobes within the stacked sandstones of the Glob alt reservoir at the East Breaks 160-161 field clearly demonstrates the need to carefully map the internal seismic facies and amplitude patterns within prospects in order to optimize prediction of sandstone occurrence. In concert with detailed fault-pattern maps, the highly compartmentalized reservoir can be delineated and wells optimally located. Additionally, seismic facies maps may suggest downflank or off-structure potential where faulting may not impose development problems. Construction of detailed seismic facies and fault pattern maps, preferably using 3-D seismic reflection volumes, results in a higher success rate of finding the closely spaced but laterally discontinuous reservoirs of gravity-flow intraslope basin plays.

Procedure

Based on the regional basin analysis as previously discussed, an exploration strategy for the East Breaks area and GOM basin deepwater areas can be defined. Here are possible steps to take to implement the strategy:

- Delineate prospective areas by looking for lowstand sand-prone areas. Use trends of isochron thicks basinward of each depositional cycle's shelf edge as a guide.

- Map seismic facies and structures of sand-prone intervals to locate prospects.

- Map amplitude patterns within prospects to optimize prediction of sandstone and hydrocarbon occurrence. Calibrate rock/physics models with local well data.

- Map deep penetrating fault and salt patterns as possible migration avenues for charging reservoirs of potential traps. Take particular note of the timing of active fault movement vs. the modeled timing of hydrocarbon expulsion from active source-rock volumes in communication with the fault.

- Calculate the risk of trap existence vs. generation-migration timing using burial history and migration avenue models.

- Locate exploration wells using detailed fault pattern maps overlain by seismic facies maps of sand-prone facies and structural maps showing closure at the top of the sand-prone seismic facies.

- Use seismic facies maps to identify downflank or off-structure potential where faulting may not impose development problems.

- As wells are drilled, place each sandstone unit encountered into its regional depositional context as a means of understanding potential reservoir continuity.

- Use computer simulations based on empirical data to predict the geology—especially petroleum system elements—beyond control points.

Locating sand-prone areas

Trends of isochronous thick synclinal fill basinward of each depositional cycle's shelf edge delineate areas in which to map seismic facies, looking for lowstand sand-prone areas partitioned by regionally correlative condensed sections. The slope facies within the low-stand isochron thicks are most likely to be sandy downslope for sand-prone shelf depocenters formed during the preceding relative highstand of sea level.

Finding prospects

Once areas of potentially sand-prone seismic facies are identified, the trapping potential of each can be assessed through both prospect scale seismic facies mapping and structural mapping of the potentially sand-prone interval. In concert with prospect mapping, mapping of deep penetrating fault and salt patterns as potential migration avenues and the calculation of trap vs. generation-migration models helps us assess the risk of specific prospects.

Drilling prospects

Once drilling has commenced, each sandstone unit encountered should be placed into its regional depositional context so that downslope or upslope reservoir potential can be correctly assessed and subsequent wells optimally located.

Potential of Glob alt and Trim A sandstones

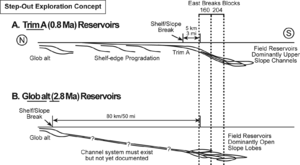

Figure 1 contrasts the depositional setting of the Trim A (A) and Glob alt (B) sandstones of the East Breaks 160-161 field. Drilling at the field encountered only channels in the Trim A reservoir, with the channel-fed lobes interpreted to occur further down paleoslope in the age-equivalent hummocky-mounded-to-sheet seismic facies. The Trim A shelf edge is mapped at the north boundary of the field. Thus, all Trim A associated sandprone facies are restricted to this minibasin. Drilled Glob alt facies include channels and channel-fed lobes nearly length::50 mi (80 km) from the mapped Glob alt shelf edge and probable deltaic sediment source from which the gravity-flow sands were supplied. Exploration potential within the Glob alt depositional sequence exists along the entire sediment transport system, as clearly demonstrated by the known occurrence of Glob alt reservoirs in the High Island-East Breaks area (Figure A).

See also

- Exploration strategy for deep-water sands

- Summary of the petroleum geology of the east breaks minibasin

- Stratigraphic predictions from computer simulation

References

- ↑ Armentrout, J. M., 1991, Paleontological constraints on depositional modeling: examples of integration of biostratigraphy and seismic stratigraphy, Pliocene–Pleistocene, Gulf of Mexico, in P. Weimer, and M. H. Link, eds., Seismic Facies and Sedimentary Processes of Submarine Fans and Turbidite Systems: New York, Springer-Verlag, p. 137–170.