Difference between revisions of "Influence of depositional environment on sandstone diagenesis"

(Initial import) |

Cwhitehurst (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

! Cement | ! Cement | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Eolian | + | | rowspan="2" | Eolian |

| Dune | | Dune | ||

| Quartz overgrowths dominate; also clay coats | | Quartz overgrowths dominate; also clay coats | ||

Revision as of 15:40, 11 February 2014

| Exploring for Oil and Gas Traps | |

| |

| Series | Treatise in Petroleum Geology |

|---|---|

| Part | Predicting the occurrence of oil and gas traps |

| Chapter | Predicting reservoir system quality and performance |

| Author | Dan J. Hartmann, Edward A. Beaumont |

| Link | Web page |

| Store | AAPG Store |

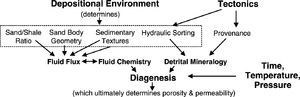

Depositional environment influences many aspects of sandstone diagenesis. The flow chart below shows the interrelationship of depositional environment with the many factors controlling sandstone diagenesis.

Sediment texture and composition

Depositional environment affects sediment composition by determining the amount of reworking and sorting by size or hydraulic equivalence. Sediments that have a higher degree of reworking are more mechanically and chemically stable. The energy level of depositional environments affects sorting by size or hydraulic equivalence and consequently produces different detrital mineral suites (Stonecipher and May, 1992).

For example, different facies of the Wilcox Group along the Gulf Coast of Texas have different compositions that are independent of their source area (Stonecipher and May, 1992). Wilcox basal fluvial point bar sands are the coarsest and contain the highest proportion of nondisaggregated lithic fragments. Prodelta sands, deposited in a more distal setting, contain fine quartz, micas, and detrital clays that are products of disaggregation. Reworked sands, such as shoreline or tidal sands, are more quartzose.

Depositional pore-water chemistry

Depositional pore-water chemistry of a sandstone is a function of depositional environment. Marine sediments typically have alkaline pore water. Nonmarine sediments have pore water with a variety of chemistries. In nonmarine sediments deposited in conditions that were warm and wet, the pore water is initially either acidic or anoxic and has a high concentration of dissolved mineral species.[2]

Marine pore-water chemistry

Marine water is slightly alkaline. Little potential for chemical reaction exists between normal marine pore water and the common detrital minerals of sediments deposited in a marine environment. Therefore, diagenesis of marine sandstones results from a change in pore-water chemistry during burial or the reaction of less stable sediment with amorphous material.[2]

Marine diagenesis

The precipitation of cements in quartzarenites and subarkoses deposited in a marine environment tends to follow a predictable pattern beginning with clay authigenesis associated with quartz and feldspar overgrowths, followed by carbonate precipitation. Clay minerals form first because they precipitate more easily than quartz and feldspar overgrowths, which require more ordered crystal growth. Carbonate cement stops the further diagenesis of aluminosilicate minerals.

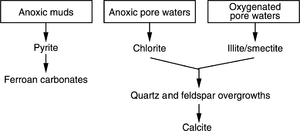

The diagram below summarizes typical diagenetic pathways for marine sediments.

Nonmarine pore-water chemistry and cements

Nonmarine pore-water chemistry falls into two climatic categories: (1) warm and wet or (2) hot and dry. The chemistry of pore waters formed in warm and wet conditions is usually acidic or anoxic with large concentrations of dissolved mineral species. The interaction of organic material with pore water is a critical factor with these waters. The depositional pore water of sediments deposited in hot and dry conditions is typically slightly alkaline and dilute.

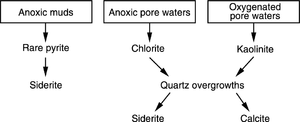

The diagram below shows typical diagenetic pathways for warm and wet nonmarine sediments.

Cements

The table below, compiled from data by Thomas (1983), shows the cements that generally characterize specific depositional environments.

| Environment | Facies | Cement |

|---|---|---|

| Eolian | Dune | Quartz overgrowths dominate; also clay coats |

| Interdune | Grain-coating clays; in areas that were alternately moist and dry anhydrite, dolomite, or calcite common | |

| Fluvial | Flood plain | Chlorite, illite, smectite, and mixed-layer clay |

| Channel | Calcite at base, grading up into calcite plus quartz, quartz plus clay minerals, and clays plus minor carbonate | |

| Nearshore marine | All | Carbonate minerals such as calcite or siderite; illite in sands deposited where fresh and marine water mix |

| Marine shelf | All | Calcite mainly; also dolomite, illite, chlorite rims, and quartz |

| Deep marine | All | Greater variety than other environments; cements include quartz, chlorite, calcite, illite, and occasional siderite or dolomite |

Diagenesis and depositional pore waters

In the Wilcox of the Texas Gulf Coast, certain minerals precipitate as a result of the influence of depositional pore-water chemistry:[3]

- Mica-derived kaolinite characterizes fluvial/distributary-channel sands flushed by fresh water

- Abundant siderite characterizes splay sands and lake sediments deposited in fresh, anoxic water

- Chlorite rims characterize marine sands flushed by saline pore water

- Glauconite or pyrite characterizes marine sediments deposited in reducing or mildly reducing conditions

- Illite characterizes shoreline sands deposited in the mixing zone where brackish water forms

- Chamosite characterizes distributary-mouth-bar sands rapidly deposited in the freshwater–marine water mixing zone

See also

- Predicting sandstone porosity and permeability

- Sandstone diagenetic processes

- Effect of composition and texture on sandstone diagenesis

- Hydrology and sandstone diagenesis

- Predicting sandstone reservoir porosity

- Predicting sandstone permeability from texture

- Estimating sandstone permeability from cuttings

References

- ↑ Stonecipher, S., A., Winn, R., D. Jr., Bishop, M., G., 1984, Diagenesis of the Frontier Formation, Moxa Arch: a function of sandstone geometry, texture and composition, and fluid flux, in McDonald, D., A., Surdam, R., C., eds., Clastic Diagenesis: AAPG Memoir 37, p. 289–316.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Burley, S., D., Kantorowicz, J., D., Waugh, B., 1985, Clastic diagenesis, in Brenchley, P., J., Williams, B., P., J., eds., Sedimentology: Recent Developments and Applied Aspects: London, Blackwell Scientific Publications, p. 189–228.

- ↑ Stonecipher, S., A., May, J., A., 1990, Facies controls on early diagenesis: Wilcox Group, Texas Gulf Coast, in Meshri, D., Ortoleva, P., J., eds., Prediction of Reservoir quality Through Chemical Modeling, I: AAPG Memoir 49, p. 25–44.